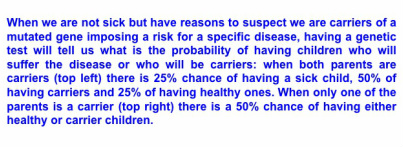

We all know that there is genetics in our lives, even intuitively when we see resemblances with our parents and grandparents, mostly physical in nature but also in character and personality sometimes. We have also been aware for centuries that if there is a disease in our family tree, chances are we will get it too. In simple terms, there is a "defective" gene running in the family which is being inherited with a certain probability. In fact, the "defect" is an alteration of the "normal" copy of the gene - a mutation or group of mutations in a gene that encodes a protein product with a specific role (for more information on these topics see “genetics and mutations” on my homepage, and the blog entry on PCR and its applications). These mutations result in an abnormal form (or absence, or decreased amount) of the protein product that this gene encodes, which, in the right context (the cells or tissue where this protein is relevant or "expressed") can lead to diseases such as cancer. What molecular biology has provided us with are tools, which become more efficient every year, to determine which specific mutations are linked to certain diseases. Once this is determined, the test becomes generally available (although this may be restricted to those who can afford it when insurance does not cover it) to people at risk. This risk, once again, is usually defined based on family history. Below is a table showing some diseases for which the mutations in the gene(s) affected are well or partially known.

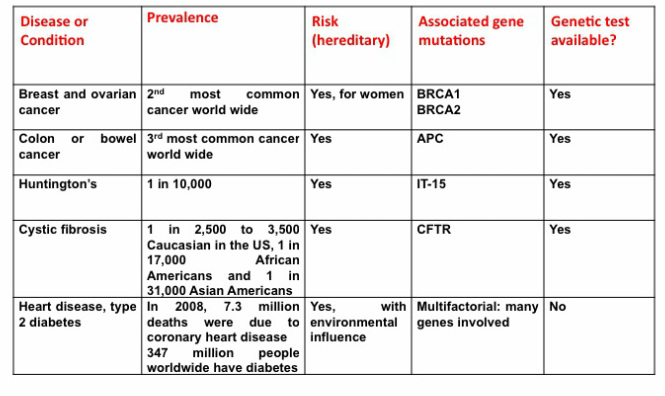

For people who suspect genetic risk in their families, they may want to be tested with their partners before trying to get pregnant. There is also a risk associated with certain ethnic backgrounds. For example, as I am about 75% Ashkenazi Jew, I got tested for a panel of possible mutations which are associated with pretty severe disorders that usually result in progressive degeneration and early death. Most of these mutations are of very high frequency in this population (about 1:100 in some cases or higher) compared to almost absent in other backgrounds. Both parents must be carriers of the “defective” (or mutated) gene for the disease for a child to get it though, so a positive test for an adult means only that he/she is a carrier. If both parents are carriers, there is a 25% chance of having a sick child (who would inherit one defective gene from each parent). This child also has a 50% chance of being a carrier (inheriting one defective copy from either parent) and a 25% chance of not inheriting any of the mutated genes, as shown in the top panel of the figure below. Another scenario (lower figure) shows the risk of passing a carrier gene to your child when only one of the parents is a carrier (50%).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed