From: http://www.thevaccinemom.com/2015/02/vaccine-shedding-should-you-really-be-concerned/

From: http://www.thevaccinemom.com/2015/02/vaccine-shedding-should-you-really-be-concerned/ There are many diseases we have never heard of anyone suffering from because there are effective vaccines against them. Some of these diseases are on their way to being (or have been) almost or completely eradicated - diphtheria, polio, smallpox, whooping cough (pertussis), measles, mumps, rubella. Because of effective vaccines available to all, in developed areas of the world disease incidence is almost negligible. In contrast, other regions have considerable numbers of cases every year, some resulting in death. According to UNICEF, almost one third of deaths among children under 5 years of age are vaccine-preventable. In 2015 about one in five infants (that is 20% of all infants or 19.4 million children) did not get important vaccines- most of them among the poorest and more vulnerable populations. In these areas, the need for vaccination is obvious, but in developed countries some people may have a hard time understanding this need. Pediatricians and schools requesting that babies and children follow the recommended vaccination schedule make it all happen smoothly most of the time. Unfortunately, some conspiracy theories supporters have negatively affected vaccination rates in recent years.

Why do we need to get vaccinated if the chances of getting sick are almost zero? Because if we don't these chances increase, and not just for us but for others as well (see below), and diseases eventually come back. Here are some examples when a reduction in vaccination rates led to reintroduction of diseases to much higher levels including deaths:

1) Diphtheria in the former Soviet Union in the 1990s: low children vaccination and a lack of booster vaccinations for adults resulted in nearly 50,000 cases (from 839 cases in 1989) and 1,700 deaths in 1994.

2) Lower use of pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine because of fear about the vaccine in:

2.1) The UK: an epidemic of more than 100,000 cases and 36 deaths by 1978

2.2) Japan: vaccination went from 70% to 20%-40% leading to a dramatic rise from 393 cases and no deaths in 1974 to 13,000 cases and 41 deaths in 1979

2.3) Sweden: incidence increased from 700 cases per 100,000 children 0-6 years of age in 1981 to 3,200 in 1985.

From http://www.mydr.com.au/travel-health/vaccination-and-antibodies

From http://www.mydr.com.au/travel-health/vaccination-and-antibodies Vaccines are designed and engineered using parts or the whole microorganism that causes the disease (virus or bacteria) after it has been “weakened”: they are killed or inactivated in specific ways that leave them unable to replicate or cause disease. Our immune system “sees” these “antigens” thanks to vaccination and produces antibodies that specifically recognize these antigens. Some immune memory "B" cells remain after this response to the vaccine ends and the antibodies disappear. The immune system later “remembers” these antigens when exposed to the live pathogenic agent that can cause disease and activates the memory B cells resulting in a much stronger and lost lasting response producing tons of antibodies. As vaccines usually result in life-long immunity, whenever we are exposed to the pathogen our immune system will mount a strong immune response which will control the infection regardless of the time passed since vaccination. Even if vaccine protection is not 100%, it will provide some protection so we do not get the full blown disease and symptoms that we would if we were not vaccinated.

The effect of a vaccine can be enhanced by the addition of "adjuvants" (from Latin: helpers) that go along with the antigens from the virus or bacteria and improve the quality and/or quantity of the immune response, although their exact action mechanisms are not well understood. Aluminum and oil-in-water are common adjuvants used in vaccines. Aluminum salts are used in DTaP, pneumococcal and hepatitis B vaccines in the US. All adjuvants (as parts of vaccines) are tested in long clinical trials to evaluate safety and purity before approval by the FDA in the US, including aluminum vaccines that have been used for over 60 years and only very rarely result in severe local reactions. We get regularly exposed to aluminum from food and water also.

The past use of the mercury-based preservative called thimerosal raised concerns about possible toxicity although no adverse effects occurred except for expected minor irritation at the injection site. Since 2001, except for some flu vaccines, no vaccines used in young children contain thimerosal.

Only smallpox has been eliminated globally. Polio is on its way, but a few countries still have cases. More than 350,000 cases of measles occurred in 2011 around the world, with 90% of US measles cases imported from another country. In 2013 however, several measles outbreaks occurred in the US including Texas and New York City in low vaccination populations. These outbreaks due to reduced vaccination rates threaten the progress made towards disease eradication.

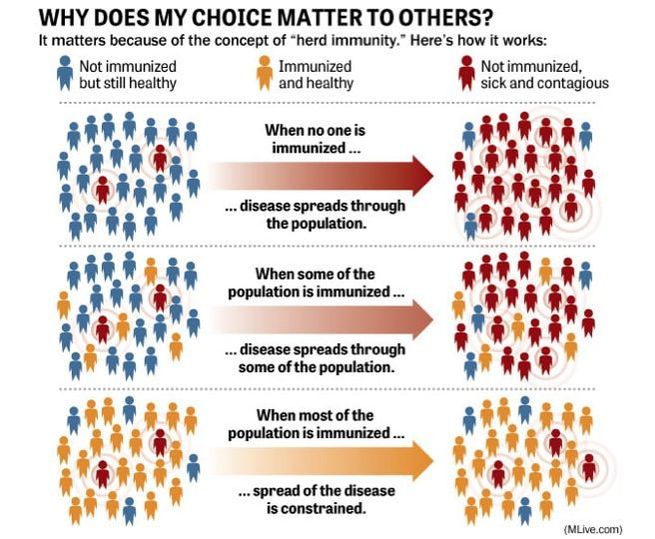

Most public health vaccination programs aim at 100% vaccination coverage. But there’s always a proportion of the population that isn’t vaccinated- babies too young to be vaccinated and people with certain conditions such as those who are immunocompromised (HIV infected or people receiving chemotherapy). However, if enough people get vaccinated among specific populations, the non-vaccinated get protection from the so-called herd immunity which basically blocks spreading of the infection to others even when some non-vaccinated get sick. The minimum proportion of vaccinated people necessary for herd immunity (which depends on several factors) is about 90-95%. How this works is illustrated on the figure below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed