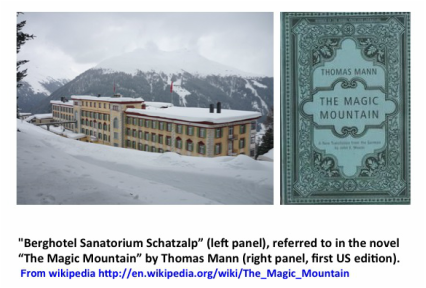

In 1882, the German physician Robert Koch discovered and identified the actual infectious agent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. At the time TB killed one out of seven people living in the US and Europe. TB was most common among young adults ages 18-35, and was characterized by loss of body weight, paleness and sunken eyes. Well known writers that died of TB in the 19th century included the English poet John Keats and all three Brontë sisters who wrote famous novels and died very young (Charlotte author of “Jane Eyre” died in 1855 just before turning 39), as well as other artists such as the Polish composer Frédéric Chopin. In the early 20th century the Russian writer Anton Chekhov, the Italian painter Modgliani and the German writer Kafka also suffered from TB. Patients diagnosed with TB were usually isolated in sanitariums; cleanliness and fresh air were thought to help the body fight and stop or at least slow the progress of the disease. I remember my first exposure to this time in the history of TB when I read the great German novel by Thomas Mann “The Magic Mountain” which takes place in a TB sanatorium in the Swiss Alps.

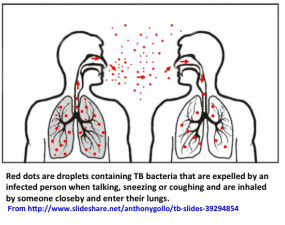

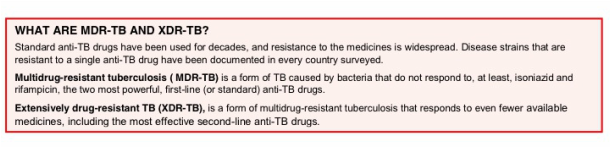

When people with active lung TB cough, sneeze or spit, the bacteria become airborne in the form of droplets that can contain hundreds of bacteria. A person needs to inhale only a few bacteria via the respiratory route to become infected. The symptoms of a person sick with “active” TB (disease) are usually a persistent cough, fever, night sweats, lack of energy and weight loss, some of which may be mild for many months. Delays in seeking care may result in transmission of the bacteria to others. Without proper treatment, up to two thirds of people with TB will die. Most people do not know that about one-third of the world's population has what is called “latent” TB, which means they have been exposed to and infected by TB but are not sick and cannot transmit the disease because they are able to “contain” the bacteria via immune defense mechanisms. From this population, about 10% may develop TB later on. However people with compromised immune systems, such as those living with HIV, malnutrition or diabetes, or who use tobacco, have a much higher risk of becoming sick with TB. Active, drug-sensitive TB disease is treated with a standard 6 months course of 4 antimicrobial drugs (usually isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide). The long duration of anti-TB treatment (even longer and more complicated when the TB bacterial strain causing disease is already resistant to some of the standard drugs) makes it difficult to comply in some cases and complete treatment, and this leads to development of drug resistance. If subsequent treatment is required for TB in the same patient and this is also incomplete, the surviving bacteria may become resistant to more than one drug, and will result in what is known as multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB. This MDR-TB, usually referring to bacteria that are resistant to the main drugs isoniazid and rifampicin, is still treatable but requires two years of treatment and the drugs used have more severe side effects than the standard ones, which can all be toxic to the liver. In addition, there is an “extensively” drug resistant TB (XDR-TB) which is even worse. Below are the WHO definitions of MDR- and XDR-TB. WHO, on an official 2014 update on the MDR-TB situation, stated that globally 5% of TB cases were estimated to have had MDR-TB in 2013 (3.5% of new and 20.5% of previously treated TB cases). An estimated 480,000 people developed MDR-TB in 2013 and 210,000 people died, whereas XDR-TB was reported by 100 countries in 2013. On average, an estimated 9% of people with MDR-TB have XDR-TB (from http://www.who.int/tb/challenges/mdr/mdr_tb_factsheet.pdf?ua=1).

But then, in the mid ‘80s the number of deaths began to rise again in developed countries due to several factors including increased immigration from TB-prevalent regions and the spread of HIV. In fact, HIV/AIDS and TB are strongly connected - approximately one out of every four deaths (25%) from TB occur in people co-infected with HIV.

The risk of progressing from latent to active TB is estimated to be between 12-20 times greater in people with HIV than among those without it (Global Tuberculosis Control 2012, WHO) and in addition, TB bacteria accelerate the progress of HIV infection. Therefore

someone co-infected with both HIV and TB, shows a faster progress of each disease. The highest rates of HIV and TB co-infection are in Africa. Nelson Mandela, at the XV International AIDS Conference in Bangkok in 2004 (http://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/cohenaids/) said:

“We cannot win the battle against AIDS if we do not also fight TB. TB is too often a death sentence for people with AIDS. It does not have to be this way. We have known how to cure TB for more than 50 years. What we have lacked is the will and the resources to quickly diagnose people with TB and get them the treatment they need.” There is currently a call for managing and implementing public health programs that include joint HIV and TB strategies in countries with high rates of co-infection.

The map below shows the countries with highest rates of TB, many of which also have high prevalence of people living with HIV/AIDS

For a great overview on the history of TB infection and its impact on human health by John McKinney, you can watch this youtube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6z7Af-ssxw

RSS Feed

RSS Feed