The disease owes its name to Dr. Carlos Chagas (1879-1934) a Brazilian researcher who found in the feces of insect vectors locally called "barbeiros" the presence of the single cell blood-sucking parasite Trypanosoma cruzi which he named after his teacher Oswaldo Cruz.

The genus Trypanosoma also includes Trypanosoma brucei that causes African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness.

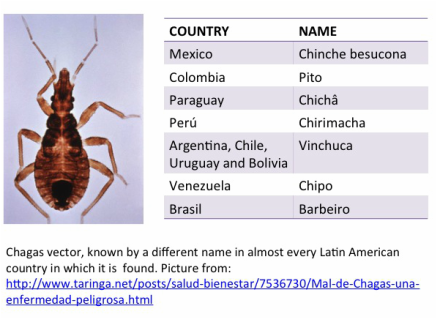

Chagas disease is spread by triatomines (see figure below for local names in different Latin American countries) also called kissing bug for its tendency to bite on the lips of sleeping people at night to suck blood. These insects are often found in houses made from mud, adobe, or straw. During the day, the bugs hide, emerging at night to eat mainly on people's faces. If infected with the parasite, they pass these in their feces. After they ingest blood, they defecate and the person can become infected when fecal parasites enter the body through mucous membranes, breaks in the skin or when the person unintentionally rubs the feces into the bite wound, eyes, or mouth.

For diseases transmitted by parasites (such as malaria and Chagas) an additional complication when studying these diseases and their causing agents in the laboratory to try to come up with drugs that may target specific stages of the disease is that the life cycle in the human host involves differentiation into specialized forms which invade specific cells or tissues. Below is a figure from the CDC illustrating these stages for bugs that transmit Chagas disease. For information on malaria you can check my malaria post.

For both malaria and Chagas, during stages in which the disease-causing parasite invades blood cells (acute stages of the disease, when the affected individual usually experiences symptoms and may go to a health center with microscopy capabilities) a spread of blood stained with special reagents onto a microscope slide can reveal the presence of the parasite, as seen in this microscope image from the CDC showing one Trypanosoma cruzi in a thin blood smear from a Chagas patient.

Tropical diseases, whether neglected or not, affect mostly the poorest people living in rural tropical areas. In general, the vectors transmitting these disease to humans (triatomines in the case of Chagas) or high frequency of infected vectors (mosquitos for malaria, dengue and Chikungunya) are not found in urban areas. Precarious hygiene and infrastructure conditions further contribute to disease spread in rural habitats. Chagas can be also be caught from eating food contaminated with parasite-infected vector's feces. However, perhaps more attention will be paid to these diseases globally as some factors may contribute to further their spreading into developed countries. For example, higher mobility of people and waves of emigration due to unfavorable economic and political circumstances in many countries (Latin Americans to the US for example) may result in infected people's incidence increasing. These individuals may be unaware they are infected as they can live without symptoms for years or even decades. As Chagas disease can be transmitted by blood transfusion from an infected person, as well as congenitally (5-10% chance of transmission from the mother to the baby), asymptomatic patients may transmit the disease this way to others. Global warming (which is leading to and will continue to result in an expansion of the range of warmer temperatures North and South of the Equator to reach more “developed” settings such as the US and Europe) may result in insect vectors for many tropical diseases covering a wider area from the Equator, and carrying corresponding parasites (or virus/bacteria) with them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed