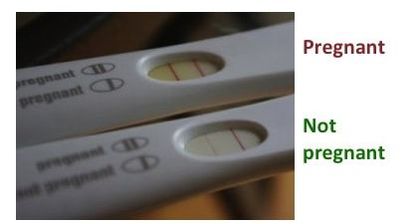

Many tests used by clinicians, laboratories or by us at home (pregnancy test or EPT) are based on the antigen-antibody interaction that occurs once the antibody recognizes its particular antigen. In the test device there is an antibody present (as well as other reagents necessary for the interaction to happen) which will recognize the antigen of an organism or cell we are evaluating. We need to provide a “sample” (usually blood, or urine for EPT, or in some cases saliva) that contains this antigen if we are “infected” or “positive” for the condition measured. Given some time for the antigen-antibody reaction to occur after the liquid sample is allowed to contact the reagents in the test, there will be some indication (color, a line) if we are “positive”. Just to make sure that all the things in the device are working well, a “positive control” is usually included, which will be a positive band indicating the test works well. The reading is read as “positive” or “negative” in medical terms. In the EPT photo below, the line on the right present in both positive (top test) and negative (bottom test) results is the positive control.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed