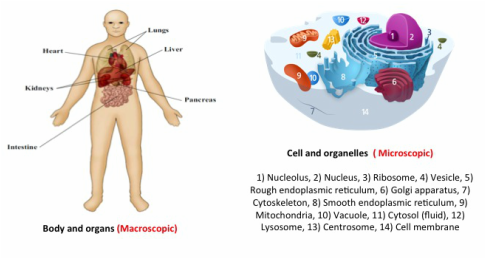

But let’s just consider our own cells, going from the outside and macroscopic to the tiny microscopic stuff inside. We have a body we can all see and talk about, think about – external, visible things like hair and eyes and shapes and sizes. This body has organs inside, each performing specific and important functions: liver, kidneys, stomach, intestines, heart, lungs, glands, brain, etc. They consist of specialized cells that are different than those of other organs so they can do what they are supposed to do.

Some organs, including glands, “secrete” hormones that are signaling molecules that travel in our bloodstream and trigger specific responses once they reach the target cells/organ which have ”receptors” for them. Insulin, for example, is a hormone made by the pancreas- an organ. In fact, not all pancreas cells produce insulin but a subset of them (“beta” cells) in a specific region of the pancreas. Insulin is very important because it allows your body to use glucose (sugar) for energy or to store it for later use. After we eat and the glucose levels rise as a result of the breakdown of carbohydrates, insulin is released. Problems with insulin in our bodies lead to diabetes - the sugar remains in the blood and there is a rise of blood glucose levels.

We keep zooming in, and we go from organs that we can still see if there is an open body of a human or other animal species member in front of us, to cells. These are now microscopic- we can not see them with the naked eye, and need a microscope. Bacteria are also microscopic, as they are single-celled organisms, although they are a bit smaller than our cells because they lack a nucleus. Cells are surrounded by a membrane, which besides keeping cellular contents protected and at the right concentrations, has channels and receptors embedded within that allow specific substances or proteins to come in or go out of the cell. Inside cells there are different organelles often surrounded by their own membranes, each with specific functions. A very important organelle that gives us energy and has its own little DNA inside is the mitochondrion (for more info see my post on mitochondria).

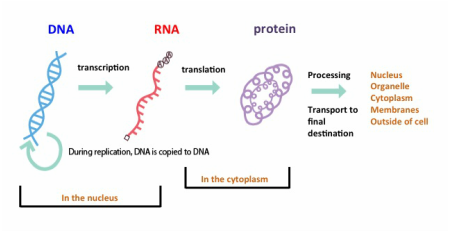

Now let’s stop for a minute and consider that all cells in our bodies contain the SAME exact DNA, which in turn holds sequences for the same genes. Genes in each cell include those that when “expressed” will allow a specific organ to be such organ as well as genes that should NOT be expressed in the same organ (or should be “silent”). This gene regulation is accomplished via numerous tightly regulated events at a molecular level that include some “epigenetics” and modifications of proteins that are involved in tightly wrapping the DNA (histones) and specific “tags” on both DNA and histones which not only vary between different cells but that now studies show they can be inherited not only from our parents but even from grandparents (see my homepage for more on this). Expression or silencing of a particular gene requires specific proteins (including “transcription factors”) whose expression is in turn also regulated. There are many cases of “feedback loop” in which amazing mechanisms sense whether or not there is sufficient amount of a certain required protein in the cell. Absence, presence, or an excess of the protein will result in the appropriate response (make more, less or none of this protein, respectively).

- Divide into 2 cells (by “mitosis”) which involves growing everything and then splitting contents, including cell membrane, nuclear membrane and nuclear DNA

- Import and export things to regulate inner contents, pH, salt concentration, food, etc

- Produce energy (mitochondria)

- Transcribe DNA into RNA, translate RNA into proteins

- Transport, degrade, import or export proteins

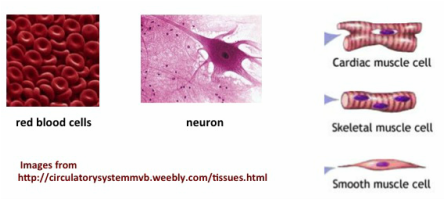

Some cells differ from others as they perform specialized functions. For example, red blood cells lack a nucleus and contain hemoglobin (which gives them a red color) in which they transport oxygen, nerve cells are long and branched into axons to transmit electrical impulses and muscle cells are elongated.

By Spencer Katz (http://www.yalescientific.org/2010/09/cartoon-apoptosis/)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed