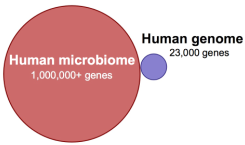

From http://laughingsquid.com/asapscience-explains-the-human-microbiome-the-microorganisms-that-share-space-with-the-human-body/ (a 3 min video and nice overview of what microbiomes are and do for you).

From http://laughingsquid.com/asapscience-explains-the-human-microbiome-the-microorganisms-that-share-space-with-the-human-body/ (a 3 min video and nice overview of what microbiomes are and do for you). About 2400 years ago, Hippocrates said: "All disease begins in the gut"

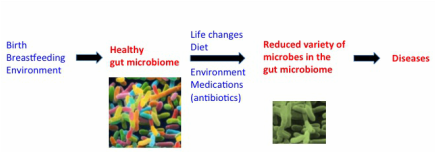

From http://mpkb.org/home/pathogenesis/microbiota

From http://mpkb.org/home/pathogenesis/microbiota

RSS Feed

RSS Feed