The growing cool trend in science involving active non-professional public participation in knowledge gathering, is variously called citizen/community/crowd/volunteers science and features prominently in a wide variety of science and research areas.

What is or isn’t citizen science is often not clearly defined, in fact there is no agreement on a globally accepted definition. Sometimes projects that gather information from volunteers submitting it online are labelled as citizen science, when these volunteers are not really doing the work of scientists but just sending their own data. These studies are no different from studies that request participation from volunteers as study subjects, except that the advertisement and data collection are done through web tools. An example of a recent project wrongly referred to by some as citizen science was one used early in the COVID-19 pandemic known as the Covid Symptom Tracker, a collaboration between US and UK scientists and doctors, and Zoe, a healthcare company, consisting of a free symptom tracker smartphone application launched in March 2020 in both countries. A Nature Medicine paper published in May 2020 showed and discussed results from 2,618,862 participants in a study using this application to report potential COVID-19 symptoms. The main finding was the loss of smell and taste as COVID-19 symptoms, and therefore authors recommended to add these to the list of symptoms that back then did not include them. These symptoms are now well known to be associated with the disease, and are frequently listed as such.

Citizen science involves non-professional scientists (lay people) with several possible roles, depending on the project, ranging from developing the research question and designing the method to contributing data, checking or monitoring, interpreting and analyzing data. Citizen science allows collection of data from widespread geographic areas over long periods of time, and promotes collaboration and interaction between scientists and citizens while at the same time resulting in a more informed, involved and engaged public.

Examples of popular and successful projects that have collected data via citizen science are:

1) eBird: a growing platform with bird sightings contributed by bird watchers around the world with many partner organizations and regional experts and managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. It is available worldwide as a free mobile app that collection of data offline, and a website to explore and summarize global eBird data.

2) Foldit: A “protein folding” web-based game launched in May 2008 for players to use the mouse to provide shapes for specific proteins was compared to the Rosetta algorithm developed by scientists with the same purpose. Player strategies ended up outperforming Rosetta algorithms, with a PNAS publication of these impressive results that included “Foldit players” as co-authors.

3) Polymath: several math platforms for different topics (Banach spaces, Polynomial Hirsh Conjecture, Bounded gaps between primes, etc) developed as collaborations among professional and amateur mathematicians to solve problems based on online communication.

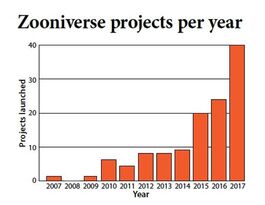

4) Zooniverse platform (este va con el gráfico de abajo on the side): Launched in 2007 with one project (Galaxy Zoo), Zooniverse has grown exponentially to 74 projects active now, 195 others paused, and 56 finished, covering a range of topics in biology, history, climate science, the arts, medicine, ecology, and social sciences. This incredibly diverse and successful platform offers current projects that you can browse and learn about including Galaxy Zoo, Chimp&See, Penguin Watch, Etch a cell, and many others.

When a project requires the collection and interpretation of data by the community of volunteers, one of the most pressing criticisms is about data quality. In these situations, data collection and interpretation are subjected to biases that may introduce error in the data and could lead to erroneous conclusions. This is because, as opposed to “controlled” experiments in which scientists standardize all aspects of data collection, citizen scientists inevitably have a variety of skill levels, knowledge, interest, and experience. For example, when asked to count objects in an image, some people may count more or fewer than others due to different levels of involvement, attention to details, etc.

Another fantastic trend in science in the past decade is the robotization of data collection and processing. We are far from being able to deploy drones or autonomous data collection devices in large amounts to survey vast areas, or to set them in place to survey for long periods of time. Similarly, our computing power, artificial intelligence and machine learning have advanced immensely in recent years but using computers to process data at the speed and with the accuracy of the human brain remains a glimmer in the horizon. In the meantime, citizen science will grow and become an important methodological approach to tackle the “difficult questions”. Furthermore, with that future robotization goal in mind, some citizen science projects use the help of volunteers to train computers, such as Soundscapes to Landscapes, where volunteers generate the data to feed artificial intelligence models in order to identify bird species in sound recordings. Perhaps in the next few decades we will see the development in many disciplines of means for lay people to train computers that then help scientists answer increasingly difficult and complex questions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed